My summer reading sometimes leads to connecting diverse topics with my area of professional focus—the built environment. I recently read a book on fasting that introduced me to the body’s recycling process called “autophagy,” and I thought about suburban retrofit. I don’t know that anyone else would make this analogy, but I think it’s apt.

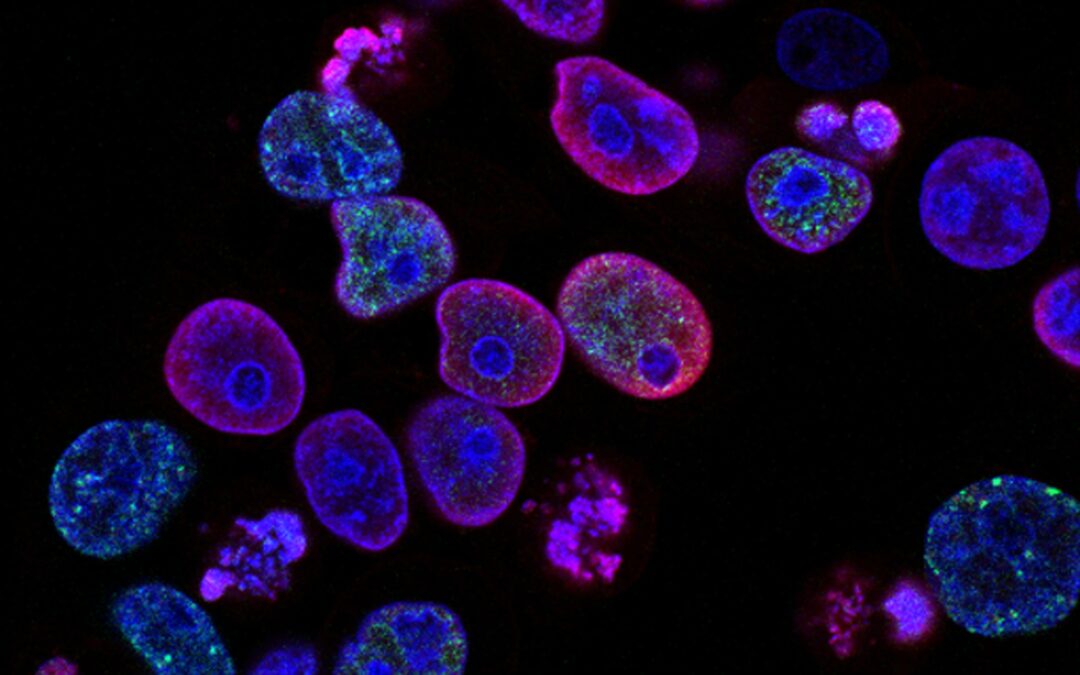

Autophagy means “self-eating,” which sounds macabre, but is the body’s vital process of reusing old, worn-out cellular parts. Recycling often produces goods of lesser or similar value—think of recycled paper—but autophagy takes our body’s junk and makes it highly valuable, using damaged cell parts for energy and building blocks for new growth. In 2016, Yoshinori Ohsumi won the Nobel Prize in medicine for work in this area.

Autophagy helps us to survive in times of extreme stress—such as starvation—but it also is important for routine health maintenance. If this process breaks down, illness such as cancer may result.

Similarly, retrofit is critical to the long-term health of suburbs. It’s the process of taking low-value elements of the suburban environment—say a defunct mall or out-of-date shopping center—and building, say, a mixed-use urban center, affordable housing, a health district, or a park.

June Williamson, coauthor of Case Studies in Retrofitting Suburbia, notes that public health and the built environment are intertwined. Suburban retrofit is linked to improving public health and promoting longevity. Projects highlighted in the book “encourage everyday physical activity; incorporate tenets of biophilia; reduce social isolation with communal gathering spaces; improve safety from various risks; mitigate ill effects from air, soil, and water pollution; increase access to healthy foods and preventative health care, and reduce the stresses of income and resource inequality,” she told Public Square.

A short history of conventional suburban development (CSD) is warranted. CSD makes up most of new development that has occurred since 1950s. Due to zoning regulations and development practices, different uses and housing types are separated from one another in a low-density pattern. Rather than a tight network of streets that is found in almost all cities and towns prior to 1950, CSD takes a dendritic (“tree-like”) form with large blocks and isolated subdivisions, where local streets lead to collectors, then to arterials. The latter thoroughfares gather all the traffic, and that’s where the commercial uses locate. CSD now makes up about 90 percent, give or take, of our metropolitan regions by area.

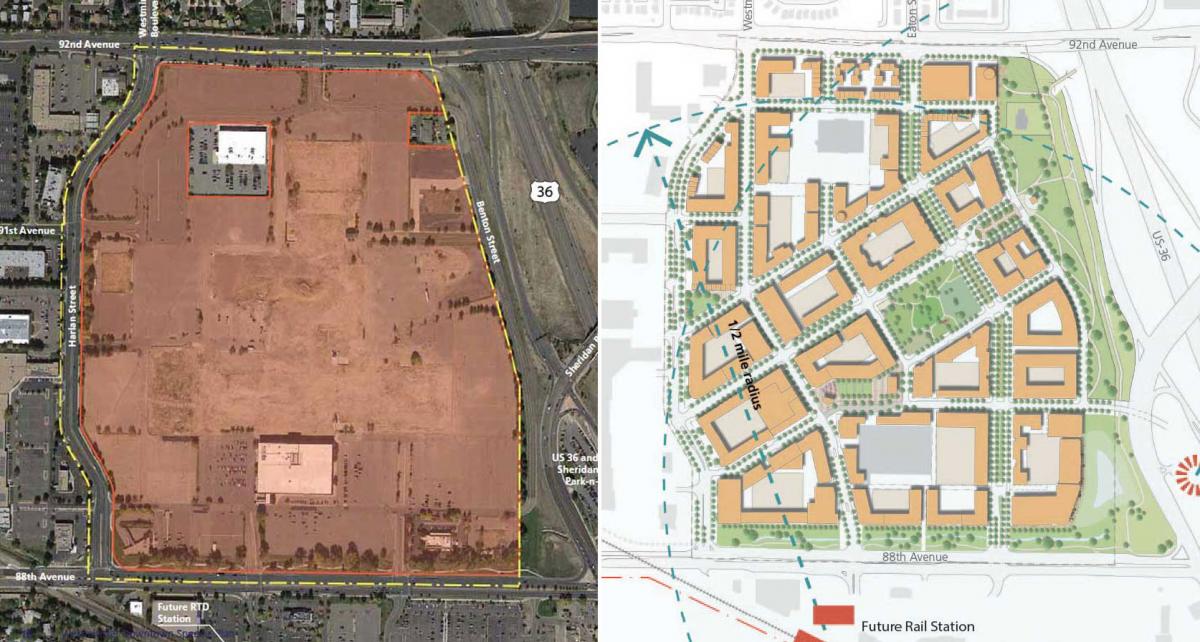

Due to the separated, low-density form, CSD has a lot of underutilized, low-value land. This is especially true when commercial properties like malls and office parks decline economically.

US suburban environments, especially if they have been around for more than three decades, are riddled with such sites. When dead and dying pieces of the built environment achieve a critical mass, they threaten to bring down the value of everything around them. That is why it is important that retrofit occur in suburbs, once they get past their first generation—30 years—of growth.

The question is, what kind of retrofit will take place? Will it be “recycling,” or “upcycling?” The latter is the process, according to Wikipedia, of creating something of greater value. Here’s a couple of examples of upcycling in a suburban environment: